How your wardrobe might be depleting other peope's water

Virtual water and responsible consumerism

Speaking of shopping, east or west, November seems to be the fittest. The approaching end of the year gives a legitimate reason for retailers around the globe to put on mega sales. Shopping festivals like 11th November in China, and Black Fridays in western countries like the US or UK, often mark the peak of the carnival. However, as water is an essential element for production of almost all goods, what is the water footprint of such frantic consumerism? What are its implications for the world through virtual water trade? How our daily life is related to global water security and sustainability? Prof Roger Falconer, chair professor of YICODE and Hohai University, shares with us his views on these issues.

I just can’t help buying more

How much water you need to consume each kilogram of these

What is virtual water and the water footprint? How is the trade of virtual water relatable to the increasing pressure on global water availability?

So maybe firstly, I can put things into a bit of context by travelling a little back, and explain why virtual water and the water footprint are important. I first got interested in this topic and global water security in about 2005, when more and more countries across the world were having more and more reports and documents written on water security. I was invited to join a Royal Academy of Engineering committee to deliver the report as the outcome of our investigations on global water security. I learnt a lot in that task, and I found it equally rewarding as my research activities ever since. So I’ve given many talks on this topic.

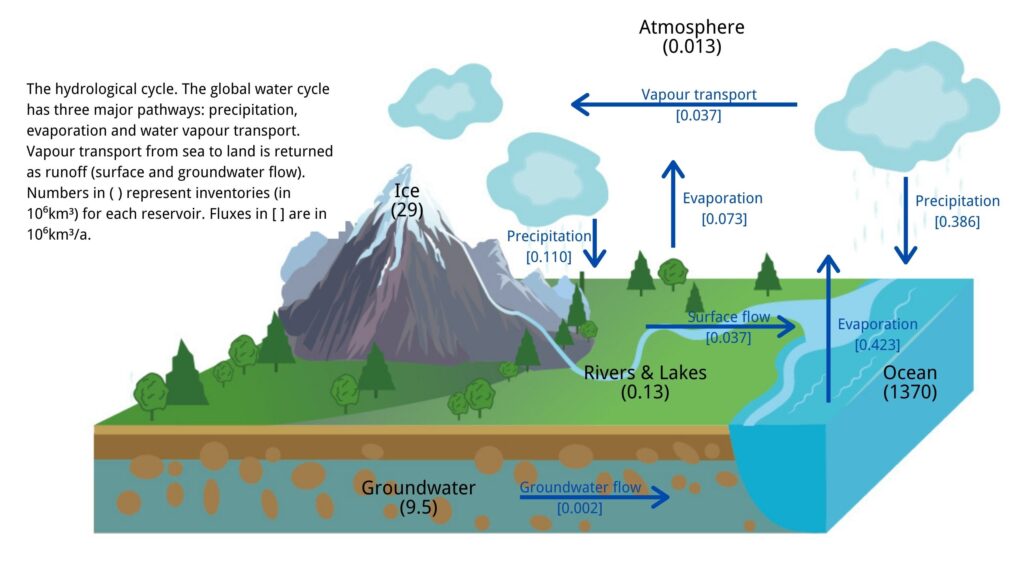

In the water cycle, we have water coming from the clouds that stay above the mountains. It then falls down as rain onto the land, then flows through the rivers as blue water. It can be absorbed in soil as green water, which can later be converted into grey water. So for a typical huge catchment, from the top of the catchment down to the coast, if we say that the rain that falls on the land is 100%, only about 36%, on average, would end up in the ocean. So what happens to the rest? We take off water from the river. The water we take off could be for domestic consumption. So it comes into the homes for showering, washing the dishes, washing clothes, and so forth. If you take that out of your river in your country, it’s your water. You’re using it and it’s up to you to clean it before you put it back in the cycle. The other thing is, though, a large amount of water is taken off the river to produce products. So it could be for paper, a car, or crops like cotton. So you do this in your country X, China, for example. You then use a large amount of water to produce, shall we say, your cotton. I’m going to use cotton as my example, if I may, because we have no cotton production in the UK. So you produce cotton, and then you manufacture clothes and sell cotton products into the UK, for example. You’ve used your water in your country to produce cotton. So when I buy a cotton shirt, and let’s assume the shirt is made in China, then all the water that has been used in manufacturing that shirt is your water. We call that virtual water of products and which has been manufactured through the use of your water.

So when we talk about the water footprint of a nation, there are two components. We have the internal water footprint, which is the water in my country, for example. It’s used in my country to feed the animals, for example, which are reared for food and then meals. The external water footprint is the water used in another country, let’s say, New Zealand, for example, which produces lamb purchased in my country. That’s virtual water. That is known as the external water footprint. Equally, we could supply goods from my country to China, for example, in which case we are using our water to produce goods to be sold to China. So the total water footprint of a nation is equal to the water used internally, that’s our own water, plus the virtual water import, that’s the water we use in China or India or Egypt to produce cotton for our country, minus any products we produce in this country using our water to sell overseas.

The first problem we have to get into perspective is that there is actually a lot of water on this planet, about 1.4 billion cubic kilometres. However, the salt water doesn’t help us in terms of water supply for domestic use, and it doesn’t help us in agriculture or food production. So we’re left with 35 million cubic kilometres of fresh water, and most of that is in ice, which is not readily available for us to use.

The natural hydrological cycle (data source: Hydrogeology: Principles and Practice, Hiscock and Bense, 2015)

We also need to bring into perspective the water–food–energy nexus. We need water to produce food; we need food to give us energy as human beings; we need water to move energy; and we need energy to move water around cities, for example. So this link between water, food and energy is crucial. Once you change one component of the nexus, you have a knock-on effect on either food or energy production. The problem is, at the moment, we only tend to focus on the water-food-energy nexus in our own countries. So people in the UK, for example, focus on questions like do we have enough energy or water here to meet our needs in the UK, or do we have and can we import enough food to satisfy our needs? And that’s the big issue.

There are some major pressures, which we have to put into context as well. We have to look at this problem of virtual water and water availability, and the stress that we could face more and more in the future around two key issues in my view. One is climate change. At the moment, we’re expecting the global temperature to increase, by the end of the century, by typically three to four degrees. The IPCC and many countries across the world, including China, are doing everything they possibly can, to reduce the reliance on fossil fuels, and try to get this temperature increase down to one to two degrees by the end of this century. That is not going to be easy. But even a one to two degree increase is going to give us a lot of additional water stress across the globe, including in the UK. The other issue, which is not often talked aboutbut can’t be ignored, is population growth. If you just take the UK for example, when I was born nearly 70 years ago, the population of the UK was only about 50 million. It’s now up to 66 million. The global population is rising. It’s currently about 7.5 billion on the planet, and is expected to rise to about 11 billion by the end of this century. So we will have to find, typically 50% more food, and for that we need more water, and we also need more energy.

Not only that, we also have a big shift in the population. In more and more countries across the world, including China, from my experience, the population is moving from the rural areas to the urban areas where the jobs are. So, the cities are getting larger and larger and we are having more and more mega cities. Most of these mega cities around the world are built right around estuaries, for example, the Thames, or on the coast. Shanghai would be an example in your country. People are becoming richer globally. China is a very good example. I have been coming to China since 1984, which was almost 40 years ago. I’ve noticed a huge change in the wealth of citizens in China. People’s diets are changing too. One kilogram of beef, coming to the water footprint, requires 15,000 litres of water to produce, while one kilogram of wheat only requires 1,300.

There are a couple of other points as well. 70% of freshwater at the moment is used for agriculture. So if we’re going to face increasing water stress in the future, how are we going to make more food? Then we will have to look at how we can make agriculture more efficient.

If I may, I’d like to digress slightly here. The world is seeing considerable investments in things like the aircraft industry, including more efficient aircraft engines, and so forth, so that more and more people have been flying, though pre-COVID obviously. Investments globally in this area are enormous. I could take many other examples, the car industry, Formula One cars and so forth. The cars have developed and transformed enormously in my lifetime. However, you see agriculture, the way in which we produce food today, is still pretty basic. We’re not really getting much more crop per drop [of water] than we did almost when I was born. That’s because it’s not seen as a particularly attractive subject to the brightest students in universities. They see developing the next Rolls-Royce or General Electric engines for the aircraft to be more efficient and so forth as very attractive. But I don’t think they see agriculture, and optimizing the crop per drop that we can get out of agriculture as particularly attractive. So you have to change this. This is, I think, is important in the context of virtual water.

We have countries like the UK for example, which is very developed. But you have to look at many other parts of the world where we see a huge amount of people suffering from health problems and even death due to water problems. We have to be mindful of this when we talk about virtual water. So let me just take a couple of examples here. 1.2 billion people on this planet have no access to safe drinking water, and 2 million young children die every year of diarrhoea. Most people in my country won’t be able to imagine that and it’s very rarely referred to in the media. Yet, if you just take the COVID crisis for example, I don’t know what the exact figures are now, but the number of deaths in the US is about a quarter million. However, the topic of COVID-19 has been on British television, day in and day out, for the last nine months. It has taken up, probably without any exaggeration, a third of the news reports. And yet the number of deaths due to COVID-19 is small compared to the number of children that have died in the same period, mainly in nations in Africa, due to very simple health problems, diarrhoea, for example, something we can solve quite easily. It’s not like a new virus like COVID-19 and so forth, where the whole world is desperately trying to get a vaccine. Without basic access to water and sanitation, women in developing counties typically walk six kilometres to get water for the children and family.

So we have the sustainable development goals (SDG). Then we have the water-food-energy nexus so that sustainable development goals, I should say, were to address. If you look at Goal 6 in particular, which is relevant to virtual water and the water footprint, the Goal is to provide access to safe and affordable drinking water and sanitation for all. That is a big challenge. I don’t think it’s presently achievable in 2030, even without COVID-19. Affordable and safe drinking water, in continents like Africa, is going to take more than 10 years to achieve in my personal view. Even in my own country, water quality in many rivers here is still of strong concern. To increase water efficiency and address water security, we need to look well beyond that, we need to consider what can do to reduce our virtual water consumption in the UK, for example,to make more water available in other countries, like Egypt, or India, and so forth. We need to ensure that grey water is cleaned before returning it to the river so that people can use clean water for sustainability in their own countries. We need to protect and restore the water ecosystem, and we need to expand international cooperation. That’s why I value my links with China, because we can learn a lot from China, and I think we have a lot to offer China as well. We also need to strengthen participation in the water and sanitation management.

When we look at the UK, for example. I hope you don’t mind me referring to the UK. It doesn’t matter. The principle is the same. We have a very high rate of consumption of water. A typical British citizen, me for example typically uses 150 litres of water a day. That’s the amount of water that comes into my house, that I use in a day, to shower, to wash my clothes, to make my meals, and so on. But my total water footprint, when you consider all of the commodities I’ve have in my home, the cars and so forth, is 4.5 cubic metres per day, in other words, 4,500 litres per day. So my domestic consumption, which everybody’s trying to reduce now, through not leaving the tap running while you’re cleaning your teeth, for example, is really small by comparison. The UK is one of the worst countries. So most of our daily total footprint, including virtual water, is extremely high. So we have in my country a huge responsibility to protect water security in the countries that supply us with products.

Now, let me talk about the water footprint. You’re talking about how much water is needed in total to produce commodities. So for example, if I have a cup of coffee, the total amount of water that’s been put into producing this coffeeto make this cup of coffee, or to make coffee beans, is 150 litres. So when I buy a cup of coffee from a store, I have consumed or effectively consumed 150 litres water. If that coffee comes from Brazil, for example, almost all that water is from Brazil as well. When we turn to a cotton shirt, for example, that tends to come from places like India, Egypt, Uzbekistan, and so forth. We have had a huge impact on those countries. In the UK, if you are producing crops, you will be using pesticides and so forth, and the water will be cleaned in general, not perhaps to one hundred percent by any means, before it goes back into the river. One of the reasons that I’m concerned is that, I can buy at a relatively cheap price, a shirt, made of cotton, produced in other counties like India or Egypt or another country. The problem is that, the water is contaminated through producing the cotton to make that shirt. It then goes back into the river, probably not treated that much. Then downstream in the river, it has a knock-on effect on the health of the people depending on the river.

So all the products we consume have water footprints. Under the growing pressures you have mentioned, how could water footprint be lowered?

So we have to ask, how can we reduce our total water footprint, which, in my view, is to do with our culture. Let’s takeChina; over the 40 years I’ve travelled to China, it has also changed its culture to follow many of western habits. For example, if I look at a man and a woman reading the news, the man could wear a grey suit, a white shirt, and a blue tieevery day. He can wear that on Monday, on Tuesday, on Wednesday, and on Thursday, not necessarily the same shirt though. Nobody in my country would criticize him for being boring because he is in the same clothes every day of the week. I don’t think we ever saw, Barack Obama, the former US president, in a picture when he didn’t wear a dark suit and white shirt, and he was photographed on television in my country probably two or three times a week. In contrast, to go back to the news reporter in the UK, the woman would be expected to put on a different dress every day of the week, and that dress might be made of cotton that was manufactured in countries other than the UK. Its production might be contaminating downstream water. I ask myself, should I be paying more for the shirt or should my wife be paying more for her dress, so that we could use that extra money in those countries to treat the water before it goes back to the river? I believe this is very important because I think it would lead to much better and sustainable water quality.

If we’re going to address the Sustainable Development Goal 6, I believe this is a really an important factor. So why does a man manage to maintain a high profile in work in the same clothes, which could be the same outfit every day, sort of almost a uniform, and yet a woman is expected to wear different dresses daily. Everybody in the UK is walking around in clothes with a high cotton content. The 66 million people in my country are having a huge impact on water security in many countries across the world from which we import cotton. So again, if I just take another example of a wedding in this country. I could wear the same suit every time to the wedding of my children and no one is going to question me for that. They would [only] say, “Roger, the same suit from last time.” But our friends coming to the wedding would expect my wife to wear a different dress. Usually those are very expensive wedding dresses too.

So it is something I think belonging to western culture. We would never see senior female figures in my country, members of the royal family, for example, wearing the same clothes regularly. When I first came to China in 1984, all the men were dressed the same, and all the women were dressed the same too. The women didn’t have any makeup on. So in terms of water security and water management, one of the best practices or policies to adopt in a country is to encourage people not to change their clothes every day. It’s the change in habits and culture, which took place in the last hundred years or so in my country, or the last 30 or 40 years in China, during which I’ve noticed big differences. For example, when you walk down the high street in China now, which is just like walking down Oxford Street in the UK, every woman has a different dress on. I don’ think this is wrong, but we have to be aware of the fact that by adopting many of these habits, you’re having very significant impacts on water security in other countries.

Based on your ideas, it appears that global sustainability is closely hinged on our culture and social norms. What roles can the public play in minimising our water footprint? How should scientists and researchers catalyse changes for better and social norms and water governance?

Let me deal with the scientific issues first if I may. On the scientific front, let me go back to the example of agriculture. You know most of our water is used for agriculture. I mean agriculture in the broadest sense, which includes agriculture for producing wine, raising animals like cattle and sheep, growing crops and so on. At the moment, the way that crops are grown in this country, let me take lettuce, for example, or cabbage, or any green crop that you eat? It’s planted in fields which could take up a lot of land. The water falls down on these fields. Much of that water goes straight into the soil and falls straight through soil into the ground water, and only a small percentage of that water is used to actually grow the crops.

Now, some countries, particularly the US, are using what they called ‘vertical farming’ or hydroponic farming. You will grow your crops vertically so you’re not using that much land. The crops are grown vertically in a room, which is like a very large glass house or factory, but with operating theatre standards in terms of health. It’s almost like an operating theatre on a hospital ward with COVID patients. You will have to go into the room fully protected. There are no pesticides inside. You don’t need chemicals to treat the plants. The figure I’ve got in front to me, states that it only requires 1% of water to produce the same number of crops as the amount of water needed for producing those crops on land. It’s 350 times more efficient producing crops from land. It doesn’t require any pesticides. The rooms are controlled with humidity, temperature and so forth, which provide perfect growing conditions for lettuces, cabbage and those sorts of crops. So on the scientific side, there are huge developments ongoing in agriculture in that area. On the other side, I think, talking to the public can also have a huge impact.

People like us have a responsibility to educate the public. So if I’m asked to give a talk to an academic audience, to IAHR for example, I’m very happy to do that, and we could discuss technical issues such as looking at faecal bacteria prediction models etc. Again, I get as much satisfaction these days talking to a complete lay audiences. In my view we could have a significant influence on the public to change their behaviour and water security on this planet. Let me give you an example. We have coffee in my country being produced in various countries in the world which I won’t name. It was almost slave labour, very cheap labour. People couldn’t even exist in their own country on the income received. It was promoted on television about major companies buying coffee from these countries and then selling it in the UK. It shocked the public to think they were buying coffee, paying quite a lot of money for it, and the people that were collecting the beans and so forth in other countries were not getting paid much for collecting the coffee beans. It’s almost slave labour. Then we had an initiative from the public in that they would not buy coffee from shops unless they had a sign outside saying ‘fair trade coffee’. In other words, they had to guarantee that the companies buying that coffee were ensuring that the people that were collecting beans and so forth were actually getting paid a decent wage. So the public would put pressure on companies to ensure that they were paying employees right down the train a fair wage. Similarly when I buy a shirt, for example, I would like to know that a certain amount of that money is being used in the other country where the shirt is produced to clean the water up after the shirt is produced before it goes back into the river. I would rather pay more to a company that can convince me, or reassure me, that the water is treated after it has been used to produce that shirt, so that the water returned to the ecosystem is of high quality. I believe that with enough public pressure companies would be required to make sure that the water is treated before it goes back into the river.

If I walk into two shops, one tells me I’m buying coffee from fair trade and people collecting the coffee in a 3rd world country are getting a fair wage, then I would rather go into that shop than the one next door, which is not offering fair trade coffee. Likewise, if I’m going to prefer to buy a shirt from a shop where they can guarantee me that the water is treated before it goes back into the river. Here I would rather pay more for that shirt than go to another shop next door which can’t give me that guarantee. That will come from public pressure. I believe that the more we can educate the public on water security globally, about the impact we have in Britain in buying coffee, for example, on the water security in another country, then the more pressure the public will put on companies to make sure that we are looking after the people in the country where they are buying the coffee from.

I think if you educate people in China, China could set a very good example to the rest of the world, and could lead the world in this regard. Bear in mind that if you buy products from other countries, expect the water to be treated properly before you buy it. As a foreign member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, I’m more than willing to contribute to this debate.

You have mentioned the inequalities between genders in terms of both water access and water footprint, and hence different implications for virtual water flows. How could we mitigate such inequalities in the broader sphere of water security and sustainability?

When I come to gender issue, I think this is the greatest opportunity of all to attract more women into engineering. We have many people in my country, trying to get more and more women into engineering, to improve our productivity and so forth. Women are very good at mathematics in general, just as good as men. They have just as much opportunity to contribute enormously in engineering as do men. Let’s take the Formula One as an example. I don’t know much of the details but I happen to watch the Formula One. I can imagine lots of young people thinking “I would really like to get involved in modelling aerodynamics for improving the engine of the Formula One car.” I’m sure that Ferrari would be keen to pick up any really promising engineer to help improve their car to ferociously compete with Mercedes next year. That’s very attractive to men in general. Young, high-flying, male students would be very attracted to improving that Ferrari car, feeling that they’ve achieved something. But is it that fantastic to have made that achievement? I would say not. The trouble is if you turn round and say, well, can we persuade that really bright man, not so much to spend his time on getting the Ferrari engine and the design of the car to be much more competitive? Would it not be better to persuade him to focus his brain on developing better agricultural systems, so that we could obtain a more efficient agricultural system? That’s so not going to be particularly attractive to women either.

Two million children are dying every year in Africa of diarrhoea, a very basic disease. Hardly anyone dies from diarrhoea in the western world. If I turn round and say to women in my class when I was teaching students at Cardiff University – you could actually save huge numbers of lives if you take your excellent academic skills and try to improve the crop per drop, we can get more food out of the limited water resources we have on this planet. You could reduce food shortage and poverty dramatically in many countries. If you put your minds to developing improved hydrodynamic modelling, biochemical modelling, ecological modelling and so forth, so that we can focus on improving the quality of water at the plant, at the farm before it goes back in the river, you could save thousands of lives downstream because the children downstream bathing in the river will be playing in water with much better quality. Then you could persuade women to come into engineering and use those brains actively to improve the water quality from the cloud right down to the coast. And then agriculture suddenly becomes very attractive because the deliverable at the end of the day is improving the water quality in the system from the catchment down to the coast, improving public health and saving lives. You would probably save more lives as an individual than any doctor would in his or her lifetime, even if we left the boys carry on trying to improve the efficiency of Formula One cars.

So when it comes to gender, I believe that the agriculture hidden behind saving lives is very attractive to women. When I was teaching at Cardiff University and running a large research team on hydro-environmental engineering we often hadmore women than men in that team, because they were interested in ecological modelling, reducing faecal bacteria in rivers, and coming up with sometimes very simple but effective ideas. For example, the best way to reduce diffuse source pollution into a river was to fence off the river, so that the cattle could not just walk into the stream and then do their business in the river, which would then be impacting on children swimming in the river some considerable distance downstream.

So I think there is a lot that we can do with agriculture to make it more appealing to actually deal with the gender issue. We can improve the appeal of the challenge by focusing on water quality and thereby delivering improved water security. If you offer projects on water quality of improving the eco-system or ecosystem services, and have that in the project title, most of the students knocking on your door saying “I’m interested in doing this project under your supervision” are women. So I do believe that addressing the gender issue in engineering could be improved dramatically by addressing the challenges of water security.

In a COVID stricken world, while governments around the globe are trying desperately to reboot their economies, some organisations are calling for a ‘green recovery’. How should the world take advantage of this crisis and think about global sustainability ?

I think COVID is a terrible virus. I look at the news in my country, and some younger people tend to have it without any problems, and recover very quickly. But many deaths occur to older people who have had long term problems. Right now in the UK we are going back into a second lockdown. So my wife and I are not supposed to leave our house for a month,other than collecting food from the supermarket and so forth. We went through a period of about three months of similar restrictions earlier this year, in March and April. So everything was closed, including all the pubs, shops and restaurants. They have been closed again until 2nd December, and possibly longer.

What has this done? I think this has made countries like my own to take stock and people questioning consumerism more. Do I need to replace this, that, and the other, say, a car, every three years? Do I need to go and buy another dress, or another shirt, or another suit? I think people are going back to basics, thinking perhaps we should think more about natureand reducing waste. I think there’s a lot more focus now on a green recovery. We’re looking to solar panels, wind power, and tidal energy. I spent probably about 10 years promoting a major project in the UK called the Severn Barrage project, which could have produced 10% of the UK’s electricity from a large barrage in the Severn Estuary. 20 years ago, that project was never really going to get off the ground. There was too much concern about environmental issues etc.. With COVID in mind in particular, more and more people are saying we should get back to looking at that project again and trying harder to address the environmental impacts. That project was actually a good idea in principle, but there is still much scope to improve the design etc. So I really do think that COVID has been a major global challenge, but it has also opened up our eyes to some opportunities. If we take one positive thing out of COVID, and that’s very hard to, I think it has made people think much more about things like virtual water.

Flying is another example. People are now beginning to say, well, after this COVID is over, I’m going to think twice about flying in the future. Do I need to fly?Another linked benefit is the huge boom in virtual meetings. I used to travel to London typically weekly before COVID came to this country, which was probably about February just after you and I met in January. Not long after I got back, we were hit by COVID. Prior to that, I would go to London, which is about 300 kilometres from my home. I would get up early to get the train from where I live to Leeds to get another train to London, to chair two meetings. I would be in London at least once a week. I used to say to people, why do we have to get up in the middle of the winter at half past five to get to London on packed trains, after which I wouldn’t get home till about nine o’clock at night. I would say to people, couldn’t we do this meeting virtually? They would say “No, no, no, no, no, it doesn’t work. You have to come to London. I think to myself in the middle of winter, why am I getting up early to go to London when the meeting could be equally efficiently run online? As a result of COVID, we don’t need to be travelling to London. The train is nearly empty here now. They will pick up after COVID, but I don’t think things are ever going to go back to what they were like before. So instead of people like myself having to go to London once a week, to chair or attend a meeting, which probably lasts typically from 10:30 to 16:00, and then not get home until nine o’clock at night, I am going to be able to chair or participate in that meeting online. That, I think, is another benefit of COVID. That will also dramatically reduce our carbon footprint, improving significantly our contribution to a green recovery. I’m not saying the benefits of Covid outweigh the disbenefits, but it has set us back to reconsider, how we can all work together globally and move towards a more sustainable and water secure planet.